Scrolling my Twitter timeline a few nights ago (yes, I still use Twitter), and spotted the following Tweet:

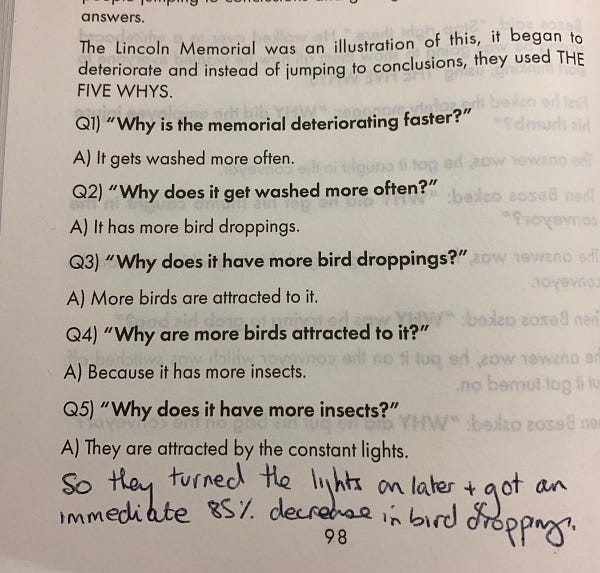

Personally, I’m a big fan of the “Five Whys” - and it is an approach I’ve tried to encourage for many years. At its core, is a mechanism to get away from solutions based on the presented symptoms, and getting to the root cause of an issue. Essentially, by continuously asking “why” (I imagine inspired by the incessant questions posed by the original developer’s children), you get to a much more resilient, effective and sustainable solution.

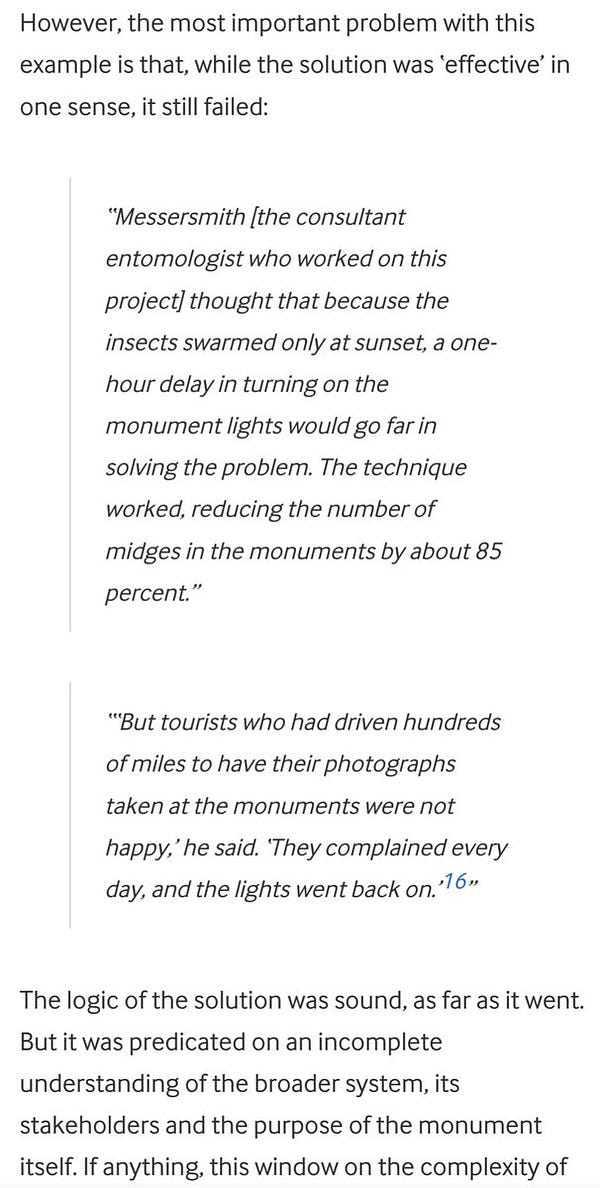

There are some that critique the method, saying that the arbitrary number 5, can sometimes lead to negative consequences, as highlighted in a reply to the above tweet:

… but arguably that is resolved by simply ignoring the superficial cap of 5 questions, a number that is deemed to be generally sufficient but not a hard rule. In the case above, a 6th question of “Why were the lights on?” would be enough to identify the potential pitfall.

In a cybersecurity context, this method is useful from moving away from the often noisy symptoms of a security incident (e.g. a ransomware attack or a big public data breach), to the underlying conditions that enabled it. This method of getting to the root cause was one of the calls-to-action of an article I wrote during my time at the UK’s NCSC:

I see this lack of investigation too often in ransomware cases, with victims chosing to remediate the incident by simply paying the ransom to get their files back - and at that point considering the incident over, but neglecting to investigate how the ransomware got there in the first place. Hearing an organisation getting hit a second time by ransomware within a few weeks or months, even by the same group they’ve just paid a ransom to, is unforuntately much more common than you’d think, as this report from Sophos outlines.

There’s another type of cybersecurity incident that often gets ignored or “pushed to the back of the queue” that merits the same treatment - cryptojacking.

Cryptojacking is the fraudulent and unauthorised use of an IT network to mine cryptocurrency - often left alone by system administrators as it doesn’t really hit against the classic CIA triad (Confidentiality, Integrity & Availability). Sure, it isn’t as sexy as a Nation State espionage operation, nor as evocative as a ransomware outbreak, and yet, it is (anecdotally at least) one of the most common and pervasive incidents I come across.

Environmental and resource costs aside (but certainly not wanting to discount them completely), the crux of the story with cryptomining, is not really with the fact that it’s taking place - much like the article quoted above, the critical question is:

“How did it get there?”

Cryptomining software doesn’t just magically appear, Pokemon-style, but often deliberately placed there. Understanding the mechanisms for how it was deployed, and how it went undetected up until now, is a powerful barometer for the general cybersecurity health of a network.

At it’s core, cryptojacking is a numbers game. A single mining set-up on a basic, run-of-the-mill PC or even server, is not going to make you a whole lot of money. Your odds get better the more powerful the devices are, or in reality for cryptojackers, simply just more devices. This is an operation that focusses on scale, and that means automation. Automation that can take over and deploy cryptomining software without needing too much human intervention. As a result, the techniques are often just focussed on easy wins - default credentials, public domain exploits for vulnerabilities often months if not years old, or even misconfiguration.

In other words, if you’ve got cryptomining in your network, you’ve probably got some basics going unresolved - and it’s better to get them fixed now, then to leave that backdoor open for a much more worrying or destructive threat actor.

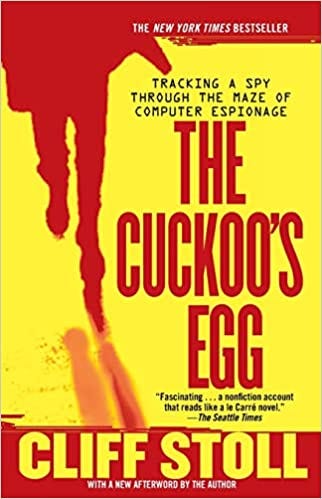

It is no great surprise that the genesis of the story in Cliff Stoll’s “The Cuckoo’s Egg” was the discovery and investigation of a 75cent accouting error. Maybe it’s further weight to the idea of “looking after the pennies and the pounds will look after themselves”…